Alabama Marble Pioneers from Scotland

Alexander Herd and Margaret Martin were married in the Parish of Ryhnd, County of Perth, Scotland on 17 December 1804 and had two daughters and six sons. Daughters Jean (1805) and Ann (1807) and son James (1811) remained in Scotland while George (1809), Alexander (1813), David (1819), John (1822) and Thomas (1827) immigrated to the United States. Alexander Sr. and son James were both Carters – builders of carts as well as Pendiclers (farmers) with a small amount of land in Ruthven Park, Parish of Tibbermore, County of Perth, Scotland. After Alexander Sr. died on 20 December 1835, Margaret lived with her son James in Scotland until his death on 9 September 1870. Margaret died shortly after James on 26 November 1870.

Links to the marble business within the Herd family is that of George Herd, brother to Alexander Sr. who was listed on the 1841 Perth census as a “Marble Cutter” at the age of 65. Uncle George more than likely apprenticed David and John Herd to the marble cutting business. Also, sister Ann’s husband, James Clement, was a quarryman in Tibbermore Parish . Thomas, the youngest son of Alexander and Margaret, was a “Wright Master” (carpenter) and returned to Scotland in 1855 and died at the family home in Ruthven Park at the age of 29 due to an “affection of the brain.”

George Herd

George, the eldest son to immigrate, was born in Tibbermore Parish, County of Perth, Scotland on 13 Apr 1809 and immigrated to America around 1835 more than likely with his brother Alexander. Brothers David, John and Thomas followed in 1842 and according to family oral tradition, they “arrived in the U.S. on the day that John’s wife was born, after six months at sea.” David, John and Thomas enumerated on the 1841 census in Tibbermore Parish, County of Perth, Scotland with their brother James as head and their mother. The occupation on the census for David and John was “Mason Apprentice.” Alexander was not on the 1841 Tibbermore census leading me to believe that he immigrated with George.

George, known for his keen business acumen, first settled in Marble Valley in Coosa County, Alabama where he received a federal land patent on 26 February 1835 for 40 acres which included a marble quarry known as the “Richard Miller and George Herd Marble Quarry.” George partnered with Richard Miller, also a native of Scotland, and began to advertise and expand their new business.

George Herd and Richard Miller purchased another quarry near Herd’s Gap in 1840 for $400. The Herd Quarry, north east of Sylacauga, near the area known as “Herd’s Gap” typically produced white marble, white marble with blue veining and some dark blue marble as well as slate. Sylacauga, “The Marble City”, lies on one of the largest known beds of the purest, white marble in the world.

The marble was hauled from the quarries in ox-wagons and then loaded on to steamboats heading toward Mobile, Alabama. The marble would then board another steamboat and make its way north via the Warrior River to Greene and Tuscaloosa Counties.

In 1842 the three younger Herd brothers arrived and the Herd brothers gradually expanded their business with additional quarries in Talladega County and offices in Sylacauga, Wetumpka, Montgomery, and Eutaw. Richard Miller and his brother Cornelius moved to Columbus, Mississippi in the 1840s and continued in the marble business as competitors. Alexander moved to Eutaw in Greene County, Alabama in the late 1840s and ran “Eutaw Marble Works” on the west side of the state.

The Herd brothers did not limit their business to marble — according to the Alabama Historical Society Quarterly,

“in August of 1839 the Coosa County Court authorized the reception of bids for building a stone jail. In January the contract was let to A. Lyle. He forfeited his contract and on March 22, 1841 a contract was made with Miller & Herd to build it for $2,745.00. It was received in August 1842. It was built of large blocks of the native granite, so abundant about Rockford.”

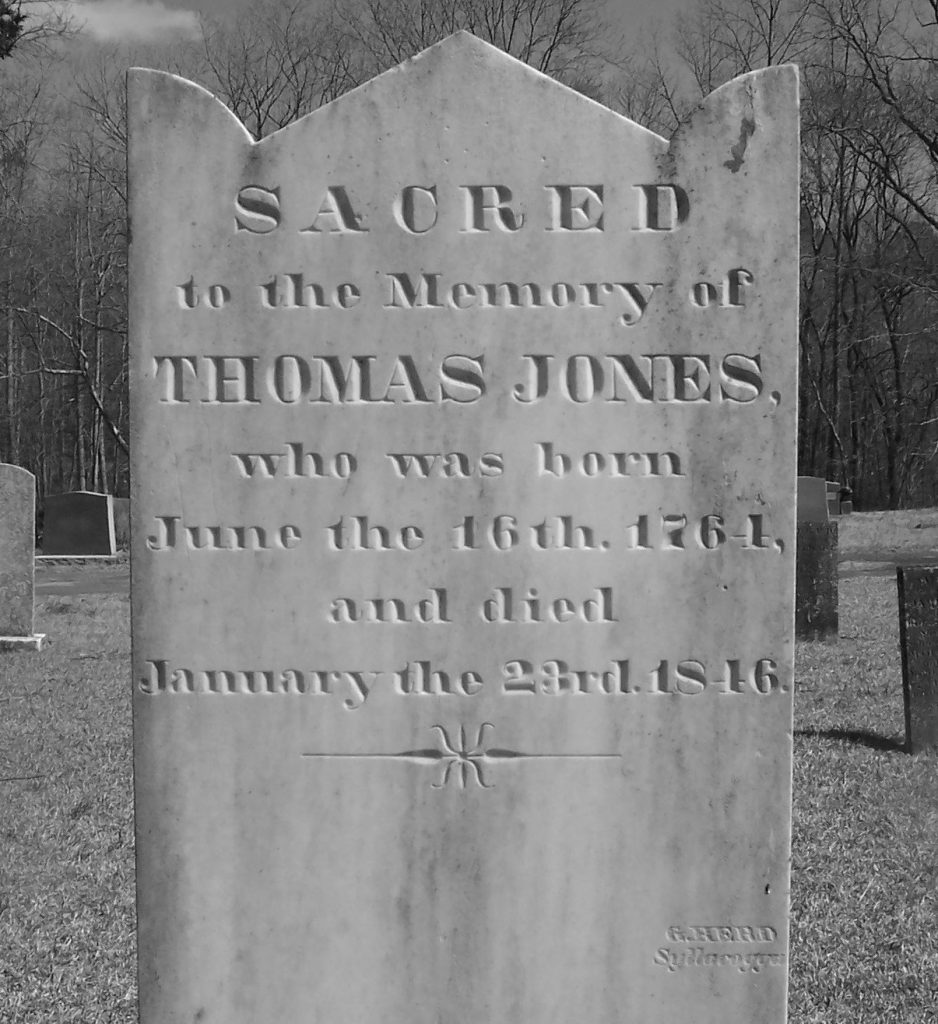

George signed the tombstones that he commissioned as “G. Herd” and inscribed a unique trademark after the inscription on the stone, making it easy to identify his non-signed stones. His signature was sometimes accompanied by a city, which may have been the office where the stone was commissioned from, and is generally found on the bottom right third of the stone. Cities with his signature include “Syllacogga” (the old spelling for Sylacauga), “Sylla. Talla. Co.,” Winterboro, and “Eutaw.”

Just when the Herd marble business reached its peak, George died unexpectedly and unmarried in 1855 at the age of 45. George is buried in the Fort Williams Cemetery with a marble obelisk monument made by his brother David.

In memory of George Herd

Who was born in Perth Shire Scotland

April 12, 1809

And died Feb. 24th, 1855

(George’s mark)

This jumbled tribute of his brother’s love

Not only imparts the spot where now he lies

But warning gives to all who hither roves

To seek in death a home beyond the skies

Leaves have their time to fall

And flowers to wither at the north winds breath

And stars to set, but all!

Thou hast all seasons for thine own, O death!

How still and peaceful in the grave

Where life’s vain tumults past

Th appointed house by Heaven’s decree

Receives His all at last

All level by the bond of death,

Lie sleeping in the tomb,

Till God in judgment calls them forth

To meet their final doom

Alexander Herd

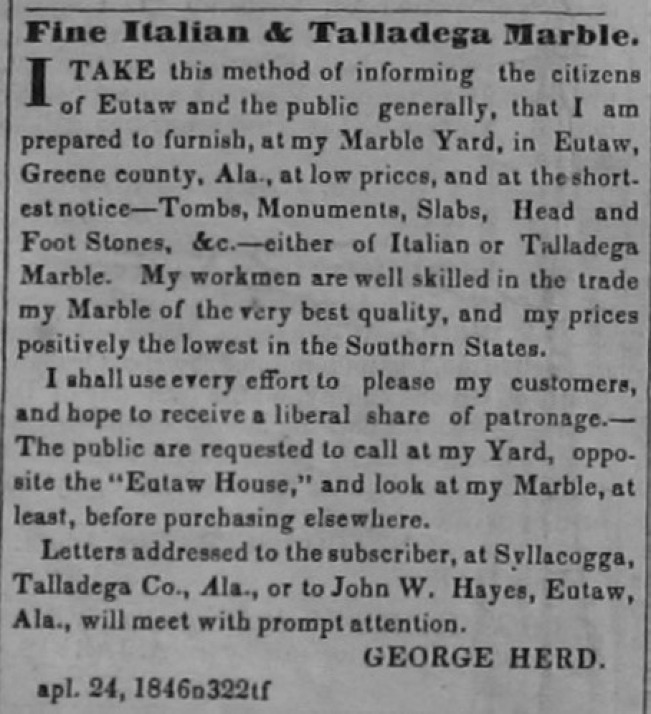

Alexander, the second oldest of the Herd brothers to immigrate, relocated to Eutaw in Greene County, Alabama in the late 1840s. Alexander initially located the marble business on Main Street in the city of Eutaw, the county seat of Greene County. George Herd placed an advertisement in the Eutaw Independent Observer in 1846 announcing the new “Marble Yard”. It’s interesting to note that they advertised marble “either Italian or Talladega” considering that they owned a number of quarries at this time.

Alexander married Margaret E. Hamlet, daughter of William R. Hamlet and Sarah M. Anderson, in Greene County on 13 July 1853. In December of 1853, shortly after his marriage, Alexander purchased a house on Springfield Street in Eutaw, which still stands and is now registered on the National Register for Historic Places as the “Littleberry Pippen” house.

Alexander sold the Pippen house and the Main Street property and purchased another Historic home now known as the “Iredell P. Vaughn” house on Wilson Street in Eutaw, behind the First Presbyterian Church in 1859. The Greene County Historic Society moved the house to its present site to the west of the church and renovated it for the use of its members.

Margaret and Alexander raised two children to adulthood; William Hamlet Herd married and became an engineer in Birmingham, Alabama and their daughter Jennie Lee Herd became a private school teacher in Birmingham and died unmarried. Their eldest daughter, Lela, born in 1854 died in 1863 and is buried in the Mesopotamia Cemetery in Eutaw near Margaret’s family.

It made good business sense for Alexander to relocate to Greene County as it was the most populous county in the state of Alabama in 1850 and was widely regarded for its thriving and elegant communities. Rivers on three of its four borders provided ample transportation for the crops grown in this primarily agricultural county. The “Golden Age” of Greene County lasted from about 1840 until the Reconstruction Era began after the War Between the States .

It also made good business sense to locate “Eutaw Marble Works” near the Presbyterian Church as much of the congregation came from the old Mesopotamia Presbyterian Church. The original church was located in the southeast corner of the Mesopotamia Cemetery and was torn down in the late 1830s when Eutaw became the County seat. A lot of his “business” came from the church.

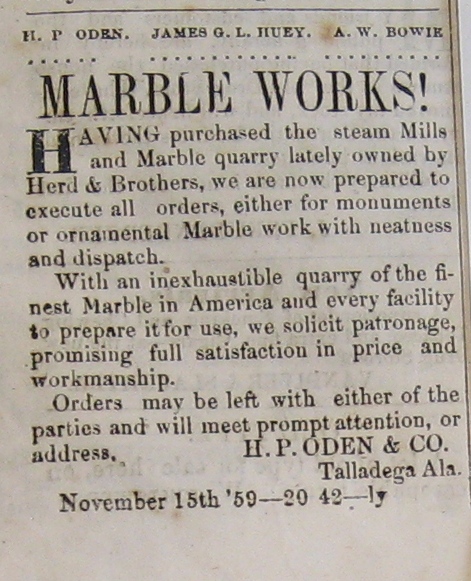

In the late 1850s the Herds began to sell their marble quarries because the marble was too soft. Henry P. Oden, a local Talladega carver, purchased one of the quarries and the following appeared in an advertisement placed in the Talladega Democratic Watchtower:

“Having purchased the steam Mills and Marble quarry lately owned by Herd & Brothers we are now prepared to execute all orders, either for monuments or ornamental Marble work with neatness and dispatch.”

Evidently, the Herds had enough problems with the soft marble that Alexander felt it necessary to advertise “he would inform the public that he uses no Talladega Marble – nothing but ITALIAN and Vermont Marble used.”

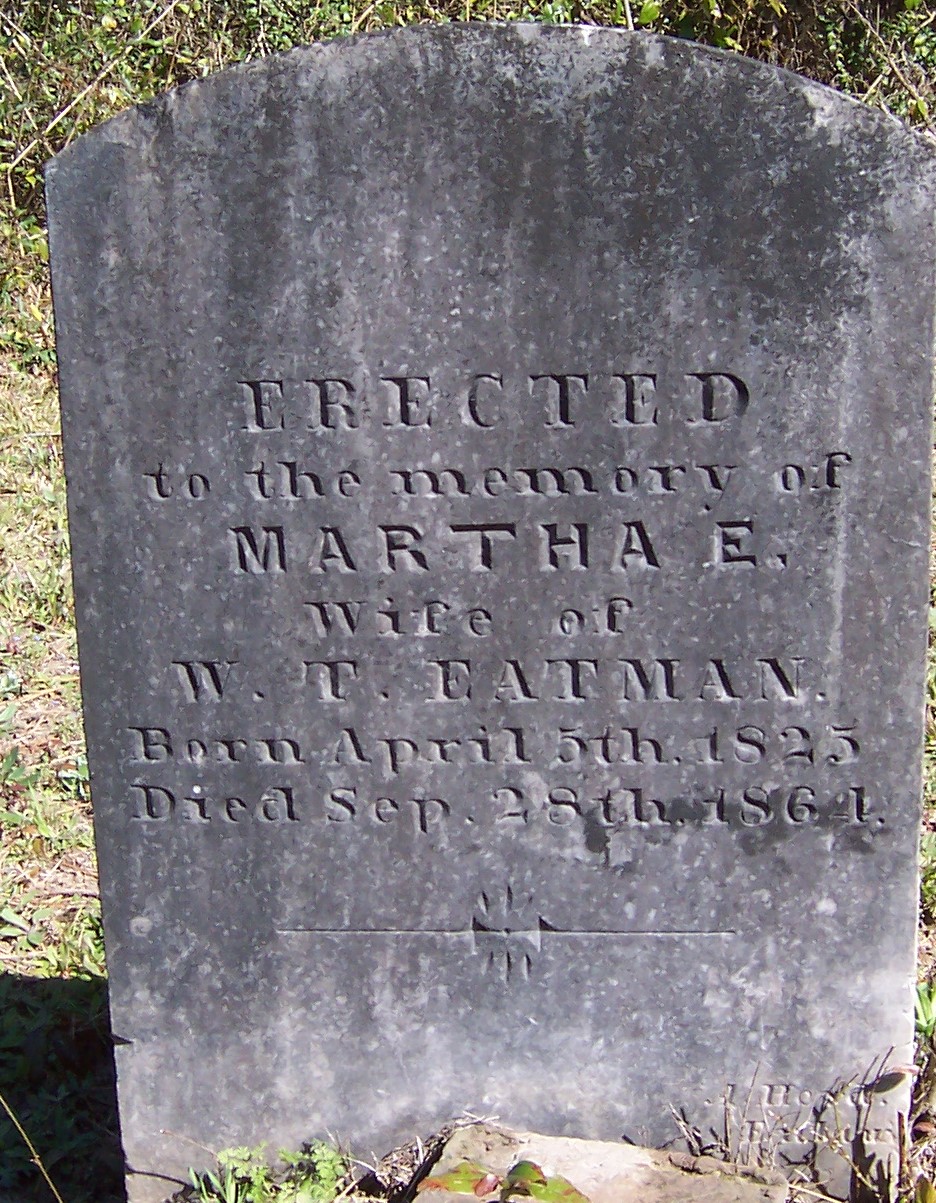

It was during Greene County’s Golden Age, before the Civil War, that Alexander Herd commissioned the majority of the known Herd tombstones in the Greene County area. The earliest stones were signed simply “Herd” or “Herd and Bros” while the later stones were generally signed on the bottom right as “A. Herd, Eutaw” or on the bottom left as “G. Herd.”

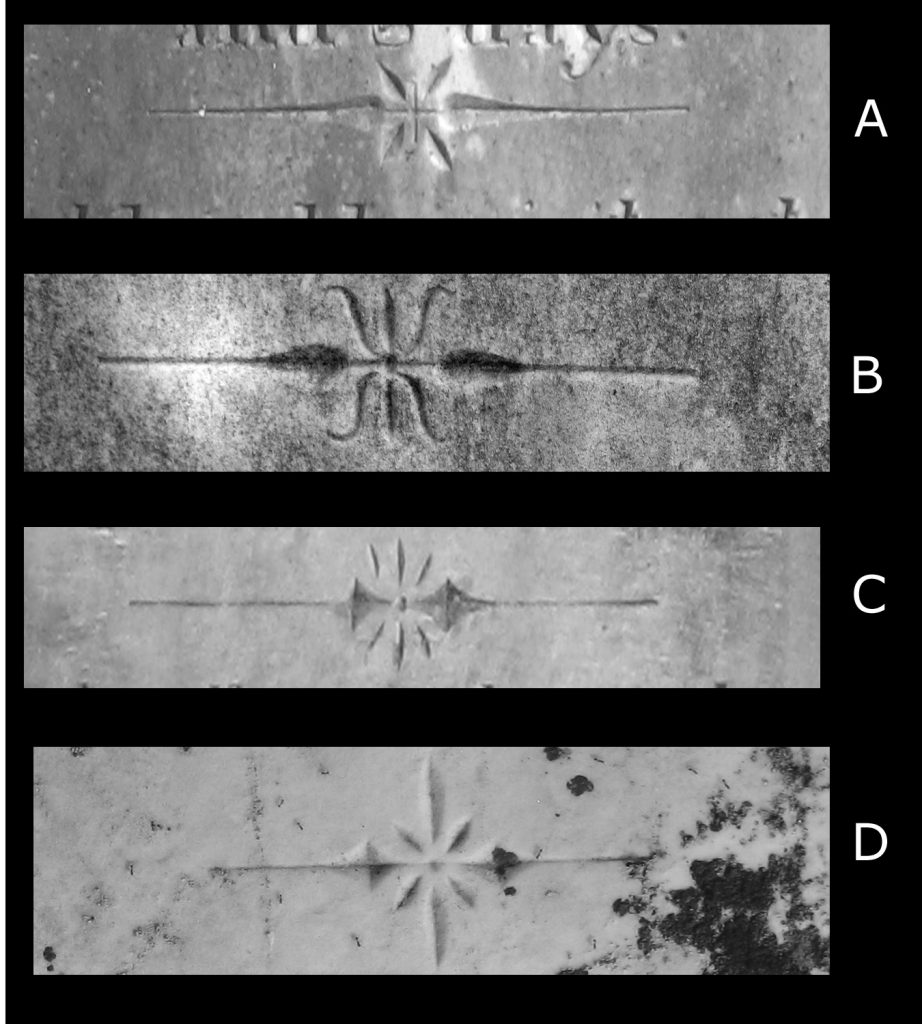

Herd stones varied depending on price, with the most common and lowest priced being an unadorned marble slab. The Herd slabs are fairly easy to identify because one of the Herd trademarks generally appeared between the inscription and the epitaph and/or after the epitaph.

A. Early Herd Mark

B. George Herd Mark

C. Alexander Herd Mark

D. Later Herd Brothers trademark which was also used by H. P. Oden & Company after Oden purchased one of the Herd quarries in 1855.

It took a while to find Alexander’s daughter Lela’s tombstone because the notion that their style was limited to “plain slabs” had become somewhat ingrained after visiting primarily remote cemeteries. Lela’s stone, in Mesopotamia Cemetery, is shorter and thicker, with carving on the outside edges. This style became more common among the Herd stones in the 1850s as opposed to the predominately tall slabs used in the 1840s.

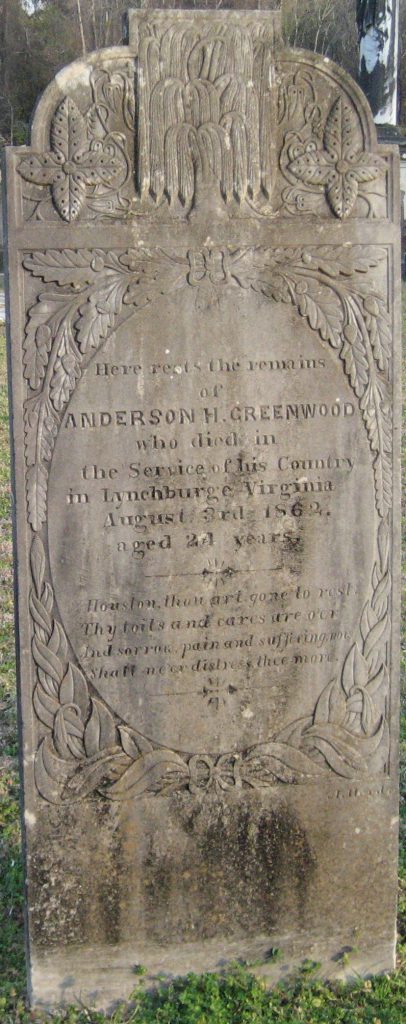

The tombstones of Anderson Greenwood (left) and Martha Scears (below), also in Mesopotamia Cemetery, are beautiful examples of more ornately carved Herd stones. Mesopotamia contains several tall Herd obelisks and many fine examples of iconography which is discussed further with David Herd, the artist in the family.

At age 52, Alexander became a 4th Sergeant in the Confederate Army under Captain Reese and the Greene County Home Guard of Eutaw . After the Civil War, Greene County’s population declined and has not yet recovered. Greene County is part of Alabama’s “Black Belt” which is a term first used to describe the dark, fertile soil. The area was perfect for agriculture and therefore a popular area for plantation owners to relocate with their slaves. After the Civil War, the term became primarily political, to describe counties in which the African-American population outnumbered the white population. The population per the 2000 census was 80% African-American, with 40% of the county below poverty levels.

Alexander and his family sold their home at a great loss and moved to Birmingham in Jefferson County, Alabama by 1876. A Greene county stone signed “A. Herd, Birmingham” indicated that Alexander was still in the marble business in 1876 after he moved to Jefferson County . Alexander died by 1879 and all sources indicate that both he and his wife Margaret are buried in Eutaw though unfortunately, their grave sites have yet to be located.

David Herd, the Artist

David Herd, born in Scotland 12 May 1819, is credited with the “artistry” in the family as well as being the first to use Talladega marble for statuary purposes. David immigrated to the United States with his younger brothers John and Thomas in 1842 after David and John completed their mason apprenticeship in Tibbermore, Perth, Scotland . According to family oral tradition, David buried $10,000-$12,000 of his and John’s $20 gold pieces just after the Civil War. Unfortunately, David died unexpectedly before he could reveal the location of the gold to his brother John. Herd descendants continue to dig around the property searching for the gold – and have not been successful to date, which is not surprising since the Herds owned in excess of 1,000 acres at the time.

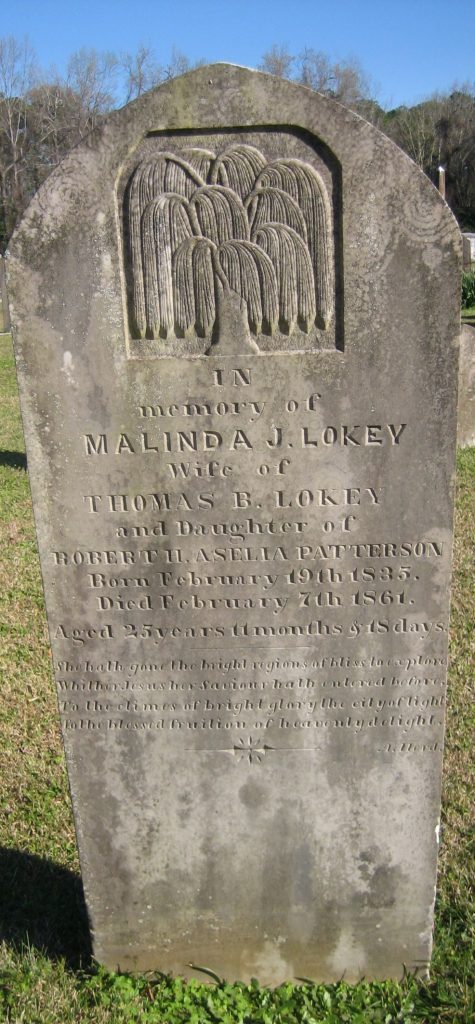

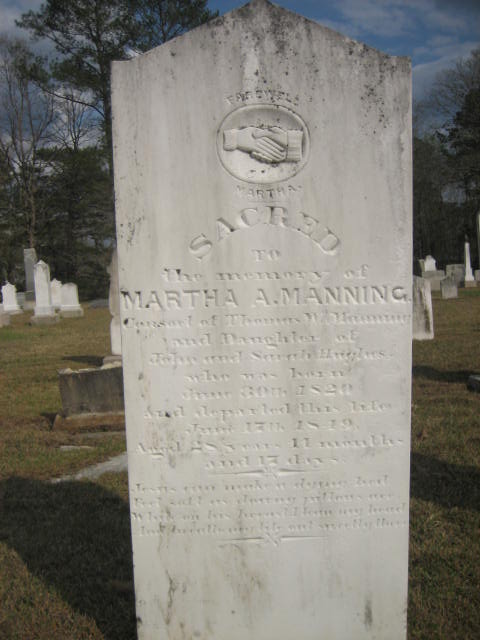

David carved many of the designs on Herd stones, while his brother John was principally responsible for the lettering. Herd designs included those popular for the period such as clasped hands, mason symbols, rosebuds and willow trees and were varied enough to suggest multiple carvers. A comparison of the willow tree found on John Alexander Rice’s grave and the willow on Malinda Lokey’s tombstone in Mesopotamia Cemetery show a marked difference in skill levels as well as style. There are some original designs among the Herd stones, such as the floral arrangement found on several stones in Greene and Pickens County and the “All Seeing Eye” design found on a fellow Scotsman’s grave in Greene County.

David carved the figure “Little Samuel” which was placed on the tombstone of his brother John’s wife 20 years after David’s death.

The willows indicate quite a variety in style, more than likely signifying a number of different carvers employed by the Herds during the forty years that they were in the marble business.

Herd iconography varied in style and was typical of the era. The Herds charged $5.00 extra for “Clasped Hands” which may explain why so many of their stones were “unadorned” in the more remote cemeteries.

David and his brother John served from August of 1861 to April of 1863 in Company K & E of the 18th Regiment, Alabama Infantry. David was lucky to survive the Battle of Chickamauga where two-thirds of his unit was killed in action. He received a minor head-wound in the Battle of Shiloh and buried his friend John Stapp, Margaret’s brother, in one of his own shirts after the Battle in 1862 .

David died at Herd’s Gap, unmarried, on 22 Oct 1887 and is buried in the Fort Williams Cemetery near his brothers George and John. His marble obelisk monument bears the signature “Rosebrough Sons, St. Louis.”

John Herd, Letters

John Herd, born Feb 1822 in Tibbermore Parish, County of Perth, Scotland, apprenticed as a mason in Scotland and arrived in America in 1842. John married Margaret Elizabeth Stapp, the daughter of John Stapp and Louisa Phillips, on 16 Oct 1865 in Talladega County, Alabama. John and Margaret raised a family of nine children in Herd’s Gap near Sylacauga.

According to a family interview, “David was the most talented sculptor but John could cut more letters in a day.”

John was fairly consistent with the inscriptions on the tombstones; the name of the deceased was almost always in uppercase at the top of the stone; the remainder of the stone was in sentence case and italics were frequently used for the epitaph. Another commonality among the Herd stones was the lack of abbreviations used for the age at death – the age was usually spelled out as can be seen on the inscription for Malinda Lokey as 25 years, 11 months and 18 days.

John died 10 January 1891 in Talladega County, Alabama and was buried in the Old Sylacauga Cemetery in Talladega County, Alabama next to his brothers George and David. While Alexander remained in the Marble business until his death, brothers David and John became farmers after the Civil War. Their descendants did not take over the family business so the Herd marble business ended with Alexander’s death.

Mary Silliman, Ebenezer Cemetery, Greene County, Alabama

William R. Hamlett, Mesopotamia Cemetery, Greene County, Alabama

Philip Beazley, Mesopotamia Cemetery, Greene County, Alabama

Mary Virginia Lightfoot, Mesopotamia Cemetery, Greene County, Alabama

Thomas Elliot, Liberty Methodist Church Cemetery, Hale County, Alabama

Robert Hill, Mesopotamia Cemetery, Greene County, Alabama

Mary C. Thomas, Clinton or Ebenezer Cemetery, Greene County, Alabama

Charles Moore Barry, Clinton or Ebenezer Cemetery, Greene County, Alabama

Hon. Thomas Crawford, Greensboro Cemetery, Hale County, Alabama

Croom Children, Greensboro Cemetery, Hale County, Alabama

Alexander C. Rice, Rice Cemetery, Greene County, Alabama

Samuel Reid, Greensboro Cemetery, Hale County, Alabama

Dr. George Perrin, Bethsalem Cemetery, Greene County, Alabama

Elizabeth Gilbert, Mesopotamia Cemetery, Greene County, Alabama

Martha A. Manning, Franconia Cemetery, Pickens County, Alabama

Herd Advertisement

James Breathwait, Ebenezer Cemetery, Greene County, Alabama

Drucilla Edwards, Ebenezer Cemetery, Greene County, Alabama

Martha Eatman, Ebenezer Cemetery, Greene County, Alabama

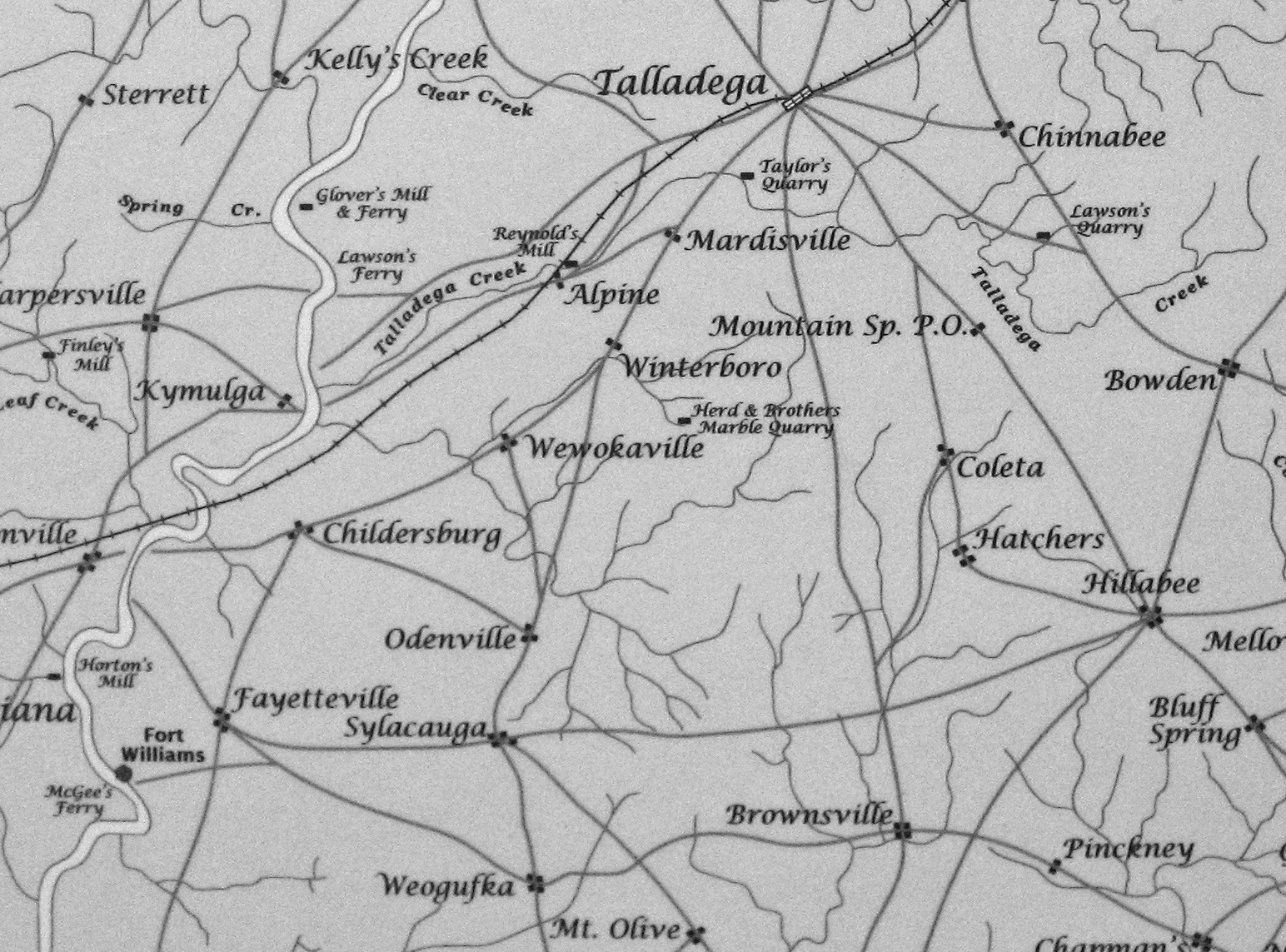

Talladega Alabama Map

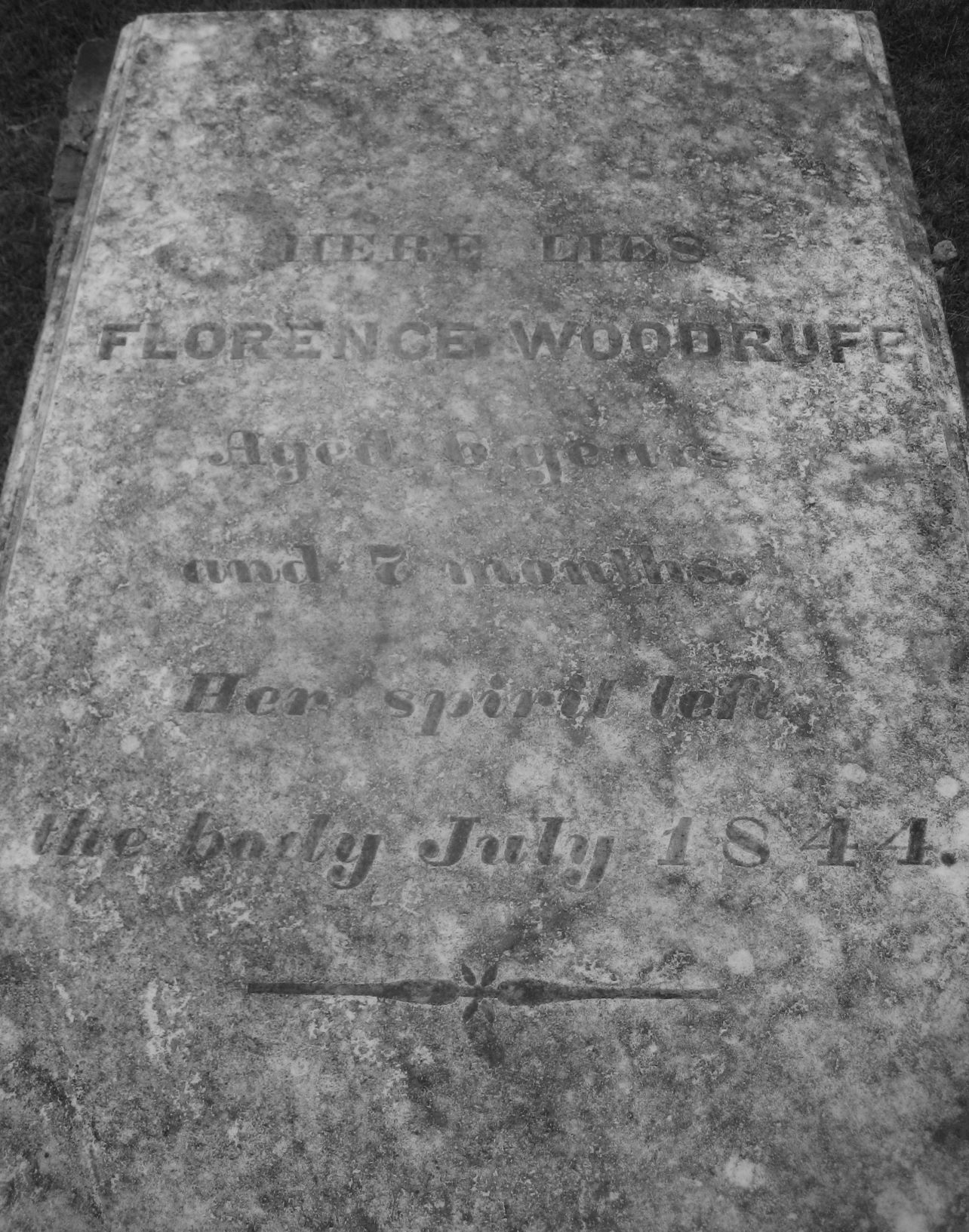

Florence Woodruff, Greenwood Cemetery, Tuscaloosa, Alabama

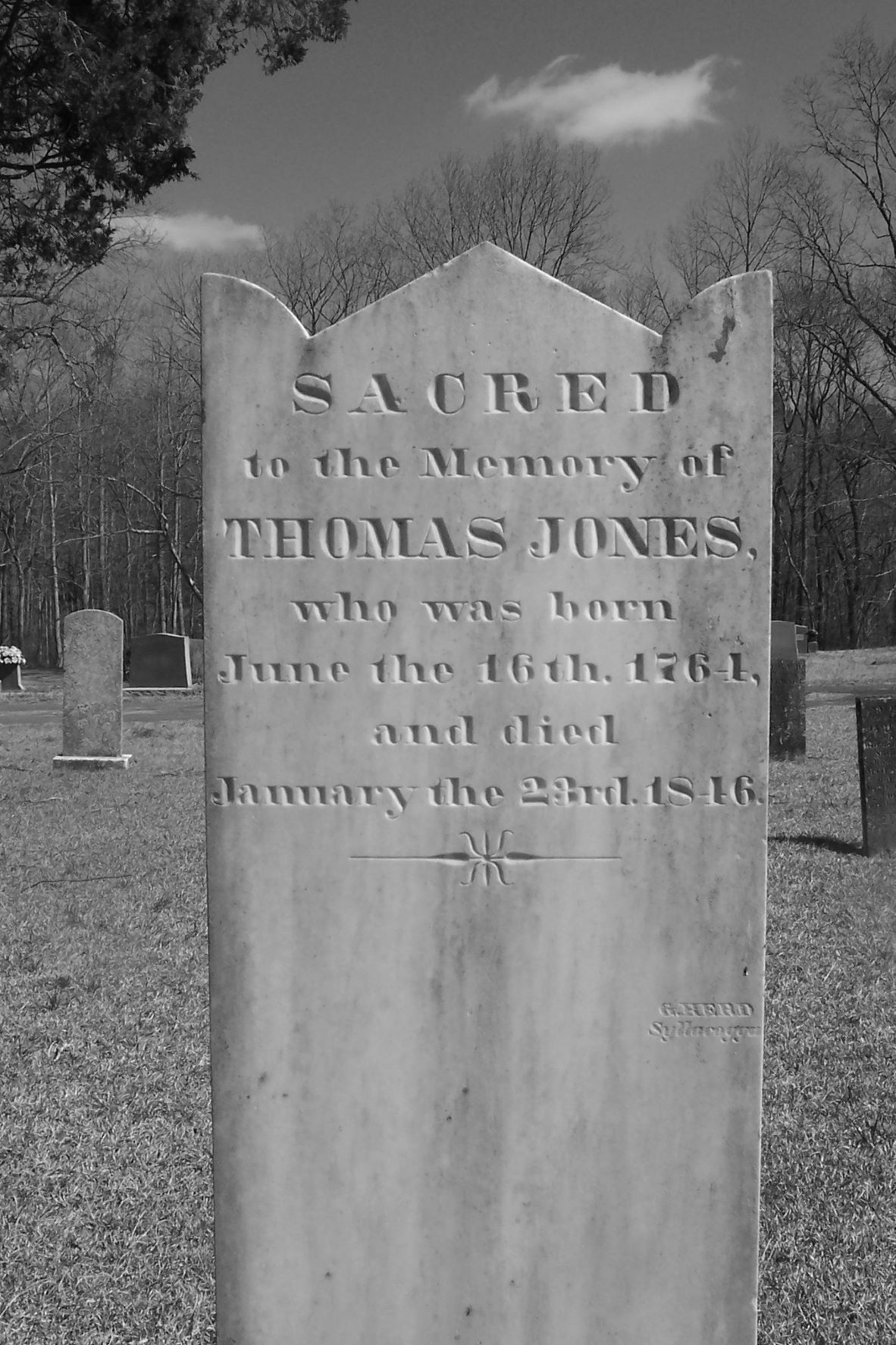

Thomas Jones, Revolutionary Soldier, Pleasant Hill United Methodist Church Cemetery