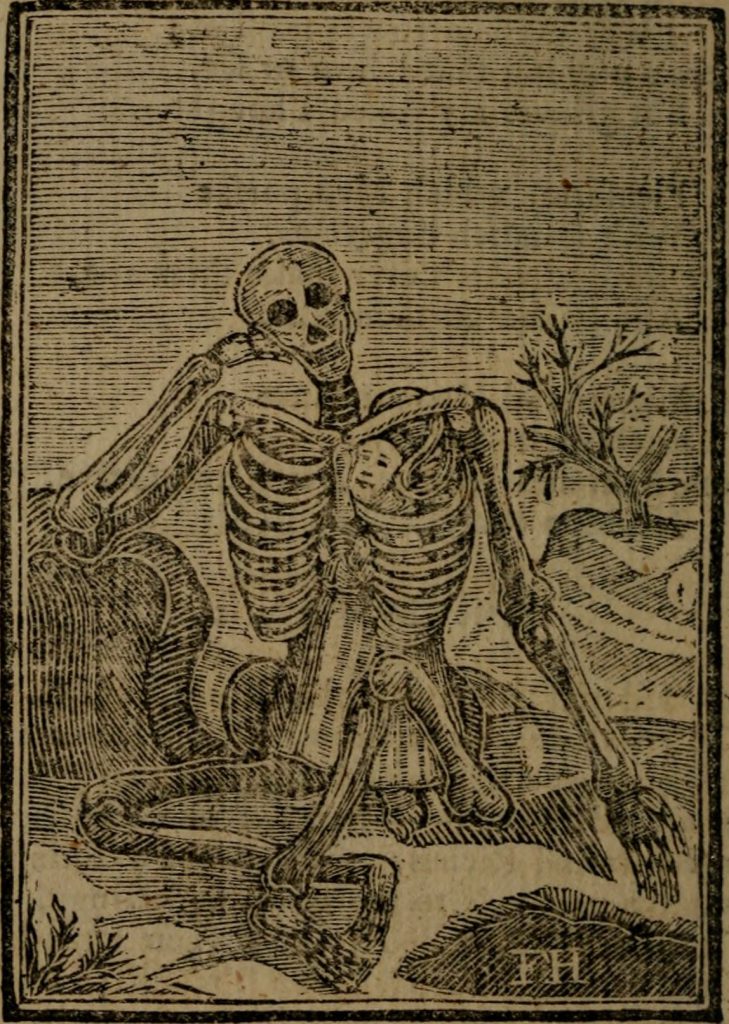

When I first saw Mehtabel Sheafe’s gravestone in King’s Chapel Burying Ground in Boston, Massachusetts I thought it was a mother skeleton with a baby skeleton inside. Crude, but certainly a way to show that the woman died in childbirth. What it really is came as a surprise! A book by Francis Quarles titled Emblems And: Hieroglyphics of the Life of Man was the source for this odd skeleton entitled “Man is Death’s Prisoner.” It is a man inside a skeleton that represents death, and it alludes to man’s (Adam’s) first sin.

Mehitabel Sheafe’s tombstone has been repaired and it is difficult to read the full inscription. It is probably a child since you can read “months” below her name rather than “years.” The “21” below “months” is probably the day she died, with the year obscured with the replacement piece. She is more than likely the granddaughter of Jacob Sheafe, d. March 1658 at the age of 42, who had the “oldest sepulchral tablet” in the cemetery according to an 1852 King’s Hill Burial Ground transcription. The oldest upright stone in the yard at the time of the 1852 transcription belongs to Mr. William Paddy, d. August 1658. His tombstone was discovered in 1830 several feet underground when some workmen were removing earth on the north side of the building.1

Considering Paddy’s long-buried tombstone, I found it interesting that Mehetabel Sheafe did not show up on the 1853 Memorials of the Dead in Boston King’s Hill Burial Ground transcription, or on a more recent transcription or on Find A Grave, which led me to do further research. Curiously, the tombstone does not appear in any literature that I could find, however, the similar Joseph Tapping stone from the same burial ground is listed in numerous publications.

It turns out that the Historic Burying Grounds Initiative, part of the Boston Parks & Recreation Department, maintained a 1,700 square foot warehouse of “stone fragments” and that they restored gravestones in 2014. Kelly Thomas, the division’s director, said the stone was discovered in 1986 while resetting another headstone. It was upside down, about 1.5 feet below grade. From that point until 2014 it was in storage with the other gravestone fragments. It had been buried for over 100 years and then put in storage! Thomas judged that it is better to keep stones with an incomplete epitaph standing up in the site, rather than to store them in the fragments collection, hoping the missing pieces will be found someday. They still have over 500 fragments in storage, so we may yet see another interesting image emerge.2

Francis Quarles (1592 – 1644) was an English poet most famous for his emblem book entitled Emblemes originally published in 1635. The poems were extended paraphrases of Biblical text with a clever epigram of four lines:3

O with what Diligence and Care

These dainty Bodies we repair!

Yet a few Years when come and gone,

Grim Death will strip us Skin from Bone

Man is Death’s Prisoner

See for what End we feed and clothe,

Cherish and pamper, please and soothe

These Bodies made of Clay;

Death’s Prisoner is every Man,

Ever since Mortality began,

And Adam was his Prey.

Thus over Man the Tyrant reigns,

And proudly all Control disdains

All Creatures him obey;

Yet, Monster, know the Time will come,

That shall decide thy final Doom,

And end thy cruel Sway.

Francis Quarles’ Hieroglyphick VI is the source for the Joseph Tapping tombstone, also in King’s Chapel Burying Ground. It is one of the highlights of Boston’s graveyard tours and is thought to be a “Masterpiece of Colonial art.”

From the Historic Marker posted at the entrance to the burial ground:

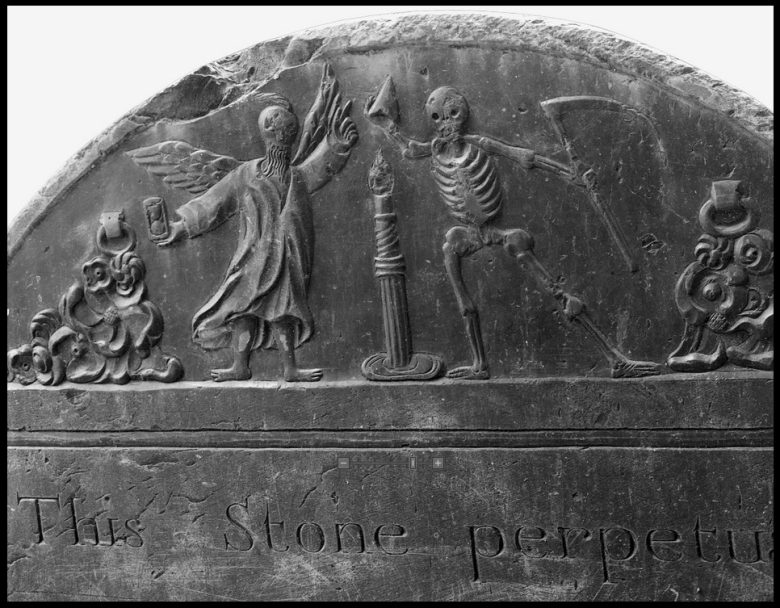

“One of the first and most famous gravestones…is that of Joseph Tapping (d. 1678). The marker is famed as a work of art conceived by the unnamed carver known as “the Charlestown Stonecutter.” The stone is one of the most elaborate in the burying ground with beautifully carved symbolic images: the skull with wings represents the soul leaving the body, the hourglass represents time running out, the skeleton snuffing out the candle is Death ending life, and the bearded figure is Time attempting to stop Death. The stone’s Latin inscriptions refer to the quick passage of time and awareness of death’s inevitability. Little is known of Tapping, a Boston shopkeeper who died at the age of 23, leaving his young wife Marianna a widow.”4

The Latin phrases “Time Flies” (Fugit Hora) and “Remember Death” (Memento Mori) are engraved on either side of the hourglass in the tympanum of the Tapping gravestone as well as a death’s head and some creative shoulder rosettes. To the right of the Quarles’ image is the Latin phrase VIVI Memor Loethi Fugit Hora–roughly “Live, ever mindful of thy dying; For Time is always from thee flying” which accompanies George Wither’s emblem XXVII in book IV of a Collection of Emblems (1630). Wither’s emblem depicts a winged hourglass topped by a skull—quite like Tapping’s and may very well be the source for Boston’s ubiquitous death’s head.5

Quarles’ four-line epigram for Hieroglyphick VI is:

Death, why so fast? pray stop your Hand,

And let my Glass run out its sand:

As neither Death nor Time will stay,

Let us improve the present Day.

The Tapping stone is thought to be the prototype for the John Foster stone (above) in the Dorchester North Burying Ground in Dorchester, Massachusetts. Foster, who graduated from Harvard around 1667, was known as “The Ingenious Mathematician and Printer.” He operated the first successful printing press in Boston in 1675 and printed the first book in Boston in 1676. His fascination with stars and physics was the inspiration for the sun in the tympanum of his gravestone.6 According to Harriett Forbes in Gravestones of Early New England, Foster’s foot stone was inscribed with the Latin verse “Ars illi sua census erat” which is translated beneath the quote as “Skill was his cash.” 7

You can view the full page for Hieroglyphick VI on Time and Death here.

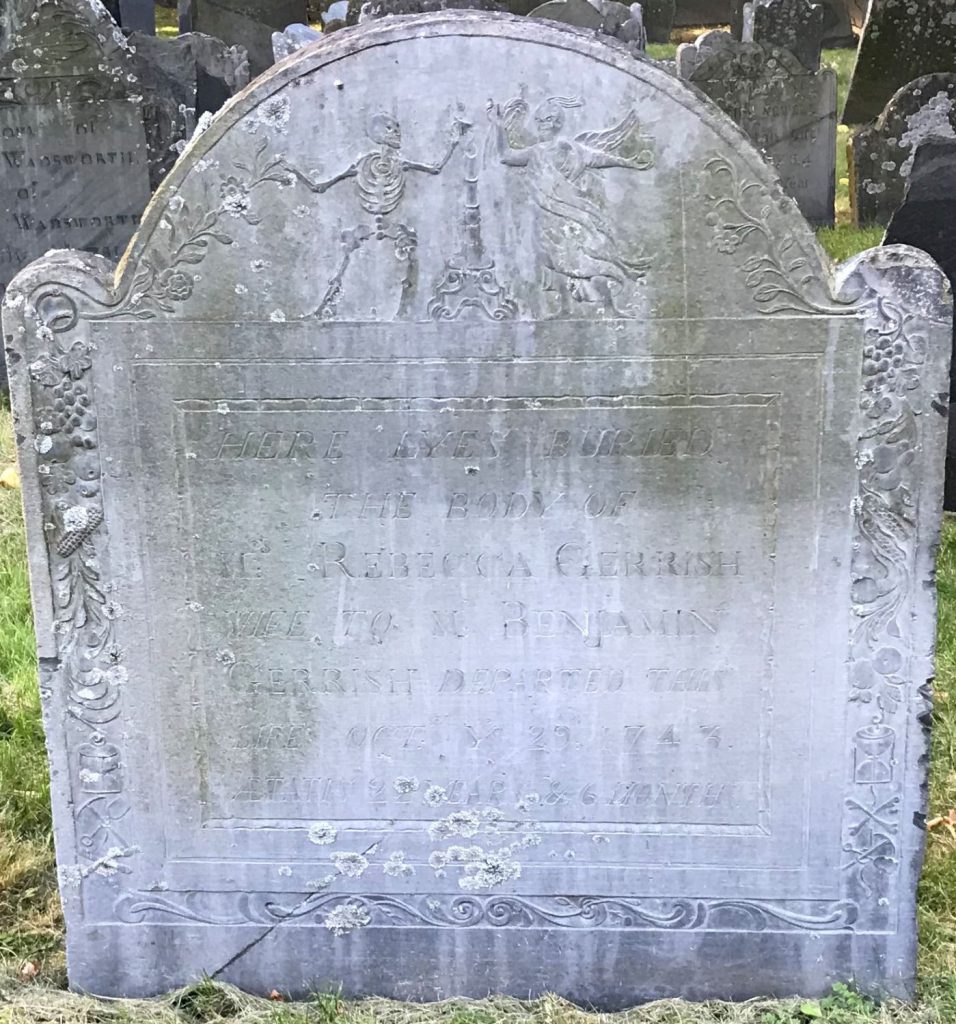

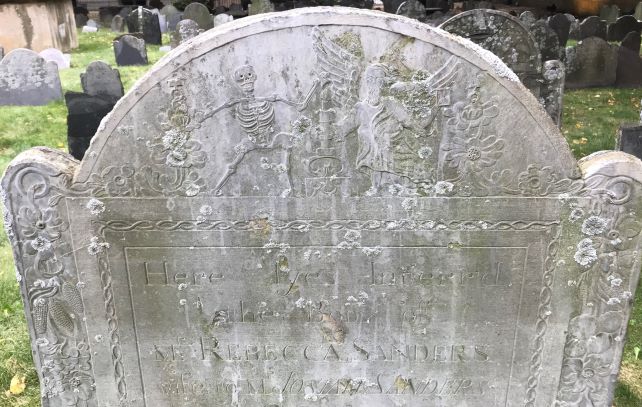

There are several other stones in King’s Chapel Burying Ground that use Quarles’ Time and Death motif with some differences. The most obvious difference between Rebecca Gerrish (above), Rebecca Sanders and Samuel and Lydia Adams stones (below) from the Quarles’ engraving is that the skeleton is on the opposite side of the candle, no longer trying to keep Father Time from snuffing out the candle of life. Father Time is supposed to look older in the Sanders depiction (bearded), since she was 86 years old to Gerrish’s 22 years. Samuel Adams was 47 years old when he died. American Antiquarian Society credits Henry (1716-1767) and/or Nathaniel Emmes (1690-1750) as the carver(s) of these three stones.8

The Charlestown Stonecutter, known as the Stonecutter of Boston, and “The Old Stonecutter” is credited with carving the Tapping and Foster stones. He is referred to as a “master craftsman” that set the standard for all later carvers. His work is found in Boston area burying grounds on tombstones dated as early as 1650 and as late as 1695, though earlier stones may have been backdated. He is credited with making major artistic changes to New England tombstones as well as developing the death’s head symbol.9 Despite exhaustive research, his identity remains a mystery. Timothy Riordan, author of The Stonecutter of Boston: An examination of his work and an hypothesis concerning his identity, presented a circumstantial case that the stone cutter’s identity is Elias Grice, based on a number of facts that he points out in the Association For Gravestone Studies Markers XXXIV.10 Grice died in 1684 and is buried in the Granary Burial Ground, across the street from King’s Chapel.

The Old Stonecutter’s work can be identified by his Death’s Head’s bulbous skull with curled eyebrows, rounded eyes, teeth, and a peculiar, triangular nose. His use of Latin quotations, rounded finials as well as the symbol before “21” on Sheafe’s gravestone leads me to believe that the Sheafe tombstone was carved by the Old Stonecutter.

The use of Quarles’ Emblems on tombstones in Scotland predate the Stonecutter of Boston’s use. Michael Bath and Betty Willsher in Emblems from Quarles on Scottish Gravestones documented ten Quarles Emblems on gravestones from the second quarter of the seventeenth century to the mid-eighteenth century. They stated that the stonecutters sometimes used more than one Emblem on one stone and rarely used Hieroglyphicks. “Man is Death’s Prisoner” was not documented in their book as being utilized on Scottish stones. In 1996, Bath and Willsher commented that the American gravestones all rely on a single emblem (Time and Death)–making the “Man is Death’s Prisoner” Emblem on Sheafe’s tombstone all the sweeter! 11

Sources:

- Thomas Bridgman, Memorials of the Dead in Boston: Containing exact transcripts of Inscriptions on the Monuments in the King’s Chapel Burial Ground, In the City of Boston (Boston: 1853), 14.

- Organizing the Gravestone Fragment Collection,” Historic Burying Grounds Initiative Newsletter, January 2013, https://www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/file/document_files/2016/12/hbgi_january_2013_newsletter.pdf; Kelly Thomas, email message to author, 6 June 2022.

- Francis Quarles, Francis Quarles’ Emblems And Hieroglyphics and the Life of Man Modernized in Four Books (Andesite Press: 2017), VI.

- The Historical Marker Database, Life and Death in Colonial Boston.

- George Wither, A Collection of Emblemes, Ancient and Moderne (London: 1635), 235.

- K. O’Neil, “The John Foster Gravestone,” Athanor X (Florida State University Museum of Fine Arts Publishing: 1991), 33.

- Harriette M. Forbes, Gravestones of Early New England (And the Men Who Made Them) 1653-1800, (New York: Da Capo Press, 1967), 113.

- American Antiquity Society, Farber Collection.

- Allan I. Ludwig, Graven Images, New England Stone Carving and its Symbols , (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1966), 89.

- Timothy B. Riordan, The Stonecutter of Boston: An examination of his work and an hypothesis concerning his identity, Markers XXXIV: (2018), 86-98.

- Michael Bath and Betty Willsher, “Emblems from Quarles on Scottish Gravestones,” Emblems and Art History Nine Essays (Glasgow: 1996), 169.